Scholastic Silver Key Awardee

Originally Published In The India Tribune (June 21, 2024)

Who am I? Where do I belong? What is my heritage? For most of my childhood, these questions have unshakably stuck with me. Defining myself, no matter how hard I have tried, has proven extremely difficult. With an Indian father and a mother whose family is deeply rooted in Michigan, grasping my identity involves reconciling different beliefs, various traditions, and two complex cultures.

For years, the process of defining myself has led me to a variety of endeavors. Self-discovery prompted me to learn Hindi on my own, hoping it would enable me to better connect with my Indian family. No endeavor seemed to work, though. My questions remained unanswered. I eat my father’s Punjabi cuisine, speak Hindi, and am captivated by stories of India (as told by my Daadi Ma, or Grandmother), but I am still not Indian enough to be Indian. I am not white enough to be white, either.

My many questions were complicated by complex family dynamics. The indisputable matriarch of my father’s family was never far away. Her home sat atop a hill in West Bloomfield, a town outside Detroit adorned with mature trees and extensive homes. At the hill’s summit was a 1970s-era three-story white house, boasting a grand foyer with expansive windows welcoming sunlight.

During my younger years, I often found Daadi Maaci comfortably perched in the lower levels, eagerly anticipating our visits. She would be seated on the 70s-style orange carpeted stairs, waiting.

Daadi Maaci, whose fond title translates to 'Grandma Aunt,' manifested a profound presence within the walls of her home. She was miniscule–under five feet tall, hunched over, and thin–but her sharp voice, striking personality, and strong nature dwarfed the large building which housed her.

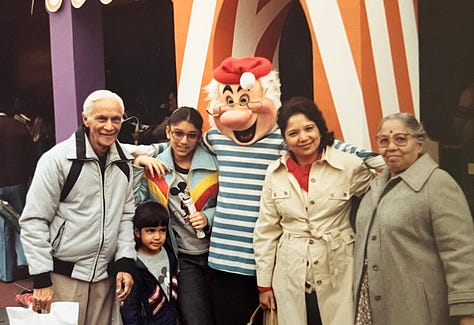

She was "like a marshmallow made on a welding machine," as Queen Elizabeth II’s mother was described by Stephen Tennant. She played a multifaceted role in my family, having adopted my father—her sister's son—when he was fifteen, providing him with education and opportunities beyond India's borders. Thus, she played a dual role in my life too—grandmother and aunt, both in equal measure.

Maaci was a mysterious figure for most of my childhood, distant and aloof. She gave an array of excuses to avoid visits longer than twenty minutes (from light pain to sleepiness). However, everything changed with the arrival of her sister (my Daadi Ma) from India during the summer after eighth grade.

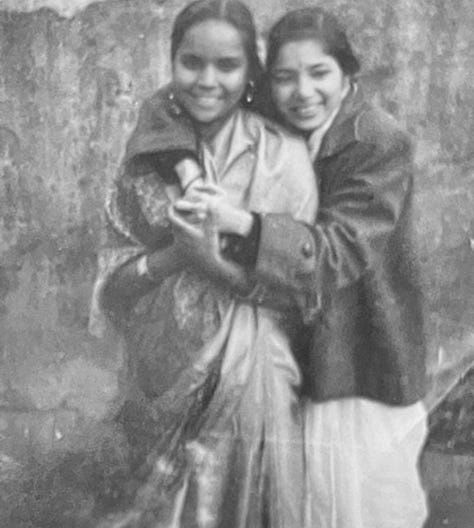

Daadi Ma and Daadi Maaci shared a deep sisterly bond, forged by the unique privilege of being the sole witnesses to each other's entire lives. Daadi Maaci was reclusive and disdainful of people, while Daadi Ma adored everything and everyone.

"Meri Bahan!"—My Sister!—Maaci exclaimed excitedly when my grandmother entered the house.

"Indira!" responded my Grandmother as the two embraced.

"I am staying too, Maaci!" I reminded her excitedly.

"Well—well, maybe, ask Dad to pick you up tomorrow?"

Taken aback, I responded, "I guess so Maaci, if that’s what you want."

"Absolutely!" she said, relieved.

Maaci transitioned into a minor ‘panic mode’ over the prospect of having two guests, leaving me irked. “She’s mean,” I told my Daadi Ma, “Just stay with us instead of Maaci.” Daadi Ma explained the situation, though, "She has been alone for so long, beta (dear)! Twenty years maybe. She will take some time."

Despite Maaci's initial reluctance, I found myself increasingly welcomed into her home over the following month. Fond of my Hindi speaking (my nickname becoming ‘the Hindi speaking grandchild’) and introduction of Shezan Mango Juice Boxes to her kitchen, her wariness transformed into genuine warmth. Through shared moments with me over tea and meals, Maaci softened. Eventually, she even texted me, asking, "When will you come and visit, dear?" Her affection reached its peak when, during my lengthy summer visits, she turned off the burning radiators in the house for me (though only momentarily).

It was strange, initially, staying in Maaci’s house. I chose her eldest son’s bedroom as my room, but I would often pop into her former office and even Maaci’s old master bedroom. Each time, I found something new—wedding photos from far-off India, a degree from Ranchi Medical College, a name tag from Albany, another from D.C., a few from Detroit—clues to who this woman was.

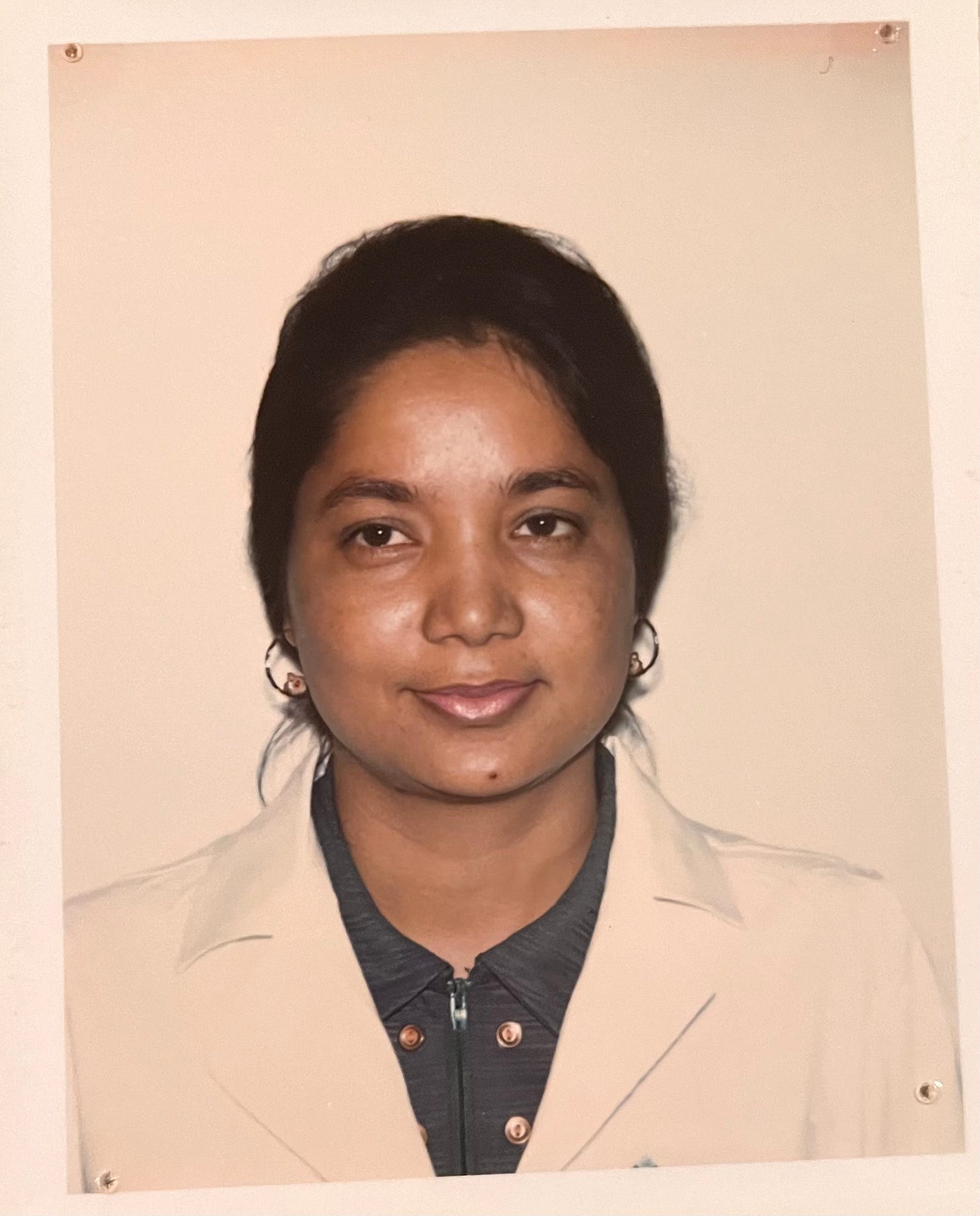

Short and thin with a light complexion, she always bore a resemblance to her Burmese grandmother, standing out among Indian relatives. Despite her appearing seemingly non-Indian, her distinct high-pitched, nasal Indian accent revealed her mixed heritage—comprising a quarter Burmese and three-quarters Indian. She, much like me, was mixed race.

There was one instance not long into my frequent visits to Maaci’s house when I found she and I were the only two awake. Hearing the whirring of Maaci’s cooling mini-fan she placed at the breakfast table, I descended the staircase to find her awaiting food.

"Can you cook?" she asked.

I looked at her, then toward the kitchen, "Well, I–"

"It’s ok. You can’t."

I quickly perked up, "No. I can."

I turned to locate supplies spread throughout her kitchen. "Vahan namak hai!"—The salt is there!—she shouted as I turned toward the sugar. At one point, as I nearly burned Maaci’s eggs, she let out an, "Aye, Meri Maa!"—a message most equivalent to ‘Good god!’

Finally, I produced two measly over-easy eggs and two pieces of toast (only slightly burned, I might add). I presented it to her with a Shezan Mango Juice Box. She lightly examined it before tasting it.

"Well, you’ll get better." she said as I laughed.

Seating myself, I began a cross-examination-like set of questions I hoped Maaci would answer.

"Maaci?"

"Haa, beta?"—Yes, dear?

"Were you scared when you first came here?"

"Where?"

"The United States!"

"Why would I have been? My husband was with me."

"After you got divorced?"

"Life changed and I changed too. I didn’t do anything special. What kind of questions are these?"

"Good ones."

"Irritating ones."

Her unassuming demeanor belied the extraordinary essence of this woman—once a standout among a mere fifteen girls at Ranchi Medical College, an immigrant doctor in Michigan, and an American success story. Following her divorce, she juggled three medical jobs to provide for her family, nurturing her own children and her sister's, offering steadfast support to relatives in India, all self-driven and sustained by her hard-earned income.

"Maaci, didn’t you once sing for Nehru?" I asked, recalling her impressive performance at the age of ten. Nehru, India's first prime minister and a pivotal leader in the fight for Indian independence, had indeed heard Maaci's voice.

"Yes. How do you know about that?" inquired Maaci, surprised by the revelation.

"I’ve done my research. Do you have a favorite song?"

"Tere Sur Aur Mere Geet."—Your Song and My Music.

Diving into my phone’s YouTube, I found the one she mentioned—a melody from the 1959 film Goonj Uthi Shehnai. The song's opening keys and bell-laden bangles triggered a smile on Maaci's face, stirring memories behind her eyes. Throughout my childhood, I repeatedly asked her to sing, fascinated by stories of her captivating voice. "No, beta." she had always said, declining my requests. Now, she joined in with the song, her voice initially wavering but soon resonating softly, as if reclaiming her history through each note.

"Beta," Maaci began, "For the questions you ask, maybe you should become a lawyer, not a doctor!" she said, alluding to her desire for all her relatives to follow in her footsteps and become doctors.

"You must be getting ladoo here. That must be why you are visiting so often." said Maaci, smiling.

"Lay-doo?" I said, confused as to the meaning.

"Ask your Daadi Ma." Maaci responded when our meal ended, as she handed her plate to me to wash and returned to her bed using her walker.

This peculiar phrase referred to ladoo, a delightful round Indian sweet which melts at the touch of the tongue. True enough, what I received was indeed sweet—a treasure trove of old stories and wisdom found uniquely around Daadi Maaci.

As I entered freshman year, Maaci’s strong work ethic and bravery as a student, doctor, and immigrant acted as a guiding light for me. To be like Maaci was a goal to strive for.

During a regular sleepover in October, I stumbled upon Maaci still awake downstairs. She expressed fearfully to my grandmother, "Mujhe thoda dard ho raha hai, Billu,"—I am in a little pain, Billu.

I quietly retreated up the orange staircase and closed myself in Maaci’s old master bedroom. Over time, as Maaci grew older and weaker, her unused room remained unoccupied while a ground-level living room was transformed into her bedroom. "Should we take her to the hospital?" inquired my dad as I heard Daadi Ma ascend the stairs.

"No–No, I am sure. Just do it tomorrow, she won’t want to leave this late." I responded, hanging up to usher my worried grandmother to bed.

The next day, while at school, I stayed in touch with Daadi Ma. Upon returning home, I was surprised to find Maaci still at the hospital at 4:00. I recall a slight fear when my uncle requested we take my grandmother to our house. Maaci usually insisted that her sister never leave her side.

What initially began as a routine appointment stretched from a few hours to a four-day hospital stay. When she came back home, I noticed her weakened state as she grasped our arms for support while climbing the stairs, step by step. During the journey home with my mother, I discovered for the first time the harsh reality Maaci was facing: stage four colon cancer.

Thus began our devoted care for Maaci, ensuring she was never left alone. Her son and my father spearheaded Maaci’s care, while I grew accustomed to the interruptions caused by the pain inflicted by this relentless disease that had begun to consume her.

India's cultural emphasis on personally caring for elders had a large impact on all of us. We ensured she was never without a family member. Over the nine months she battled cancer, she spent merely three hours alone in her house. She was always in someone's company, sometimes mine. I helped Maaci track her medicine throughout the day, usually Ativan and Motrin, or a Morphine patch, carefully noting everything in one of her little notebooks. With each visit, my knowledge of Maaci grew, while she simultaneously withered away.

Days blurred together as the family tended to Maaci's needs regularly. After countless days of freshman classes, my dad would bring me to visit her house. I’d offer her a gentle hug and discuss her life with Daadi Ma.

When the local hospital and pharmacy failed to deliver Maaci’s medicine, I took charge, spending three hours at Maaci’s house on the phone with the pharmacy, advocating fiercely for her needs and negotiating with representatives. "Her name is Indira K. Sawhney. I-N-D-I-R-A," I repeated. Finally, the medicine arrived.

Her requests were simple. "Can you bring me dosa, beta?" she asked, desiring the simple pleasure of an Indian snack she once savored as street food. I made efforts to bring her small joys, arranging for her brother in India, whom she hadn't seen since 1984, to write her a letter expressing his love and gratitude for the sister who had extended ongoing financial support and kindness.

"How could I have eaten if my brother was hungry in India?" Maaci said when the note arrived, solemnly touching its blotted ink to her head.

The second Sunday in January, the Sunday before Maaci’s birthday, held significance. Faced with the challenge of finding something to give her, a woman who wanted little, I searched through my memories of her from the preceding months. We knew, deep down, that this birthday in the ultimate chapter of Maaci’s life could be the last.

In Hindi, I wrote "Janamdin Ki Shubhkamnaye"—Happy Birthday— on a card. Then, I created a wooden clipboard-turned-picture frame, adorned with origami flowers and a photo collage of memories from India, Michigan, and beyond, reflective of the array of events which had made up her life. I crafted two cards, one in Hindi and another in English (inscribed with the message "You’re as sweet as ladoo"), and I presented a cherished bottle of butter pecan ice cream and wrapped chocolates.

Arriving at Maaci's house, we found her resting, but something was different. She snapped, "Don’t bother me! I am in so much pain, you can’t believe!" Her behavior had noticeably changed since her sister went back to India the previous month. The day her sister left, I slipped into the house to grab a water bottle and heard Maaci weeping. It struck a small pang of fear into me to hear such a strong person in such anguish.

Her birthday was celebrated that Sunday evening once she recovered. We shared quintessential Indian Masala Chai, and she carefully placed the gifts by her bed, using her strength to dig into the frozen ice cream while speaking a mix of Hindi and English.

"How old are you?" I asked Maaci. Like many people born in British India, records left discrepancies regarding age.

"Never, ever, ask a lady her age!" she responded.

"Duly noted."

"You know," she began, "I owe everything to my parents."

"How so?"

"It was my mother’s idea that I become a doctor. Even as a lady doctor, I didn't bother about opinions because that's how my parents raised me," she said as she strained to dig into her ice cream.

"You worked so hard, Maaci," I assured her.

"I owe them everything. You have no idea, beta."

Maaci possessed a keen awareness of her final journey, yet the notion of her departure never entirely resonated with me. Death was an unfamiliar concept, its certainty unexplored in my thoughts. The idea of her completely disappearing into an unknown realm seemed improbable to me, though she pondered it often.

We prayed for her following Hindu rites, which offered solace in the most desperate times. My grandmother and I prayed to Lord Shiva, spreading four coconuts into a river (though I could not fathom what we were doing) in a holy appeal for Maaci.

Several distressing moments stood out, like when she lost her iconic voice, once used to sing for India's Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru. Another time, she fell but insisted on keeping it secret, assuring us, "Nothing happened!" in her reserved manner. She'd softly express, "I am dying." She spent most of her time asleep, prompting me to ponder her thoughts during those nine months.

When my mother received a call from my father staying overnight at Maaci’s on a July Tuesday’s twilight, an unsettling sense of anxiety gripped me. Suddenly, the end of her final journey was all too real. The next day, Maaci was transferred from her home to Henry Ford Hospital in Detroit, where the proud skyline of the city she entered half a century prior was visible.

That night, as I hurriedly joined my dad at Maaci's house to collect necessities, the weight of the moment struck me. It was the first time I saw my tough, six-foot immigrant father close to tears. "She filled this place," he said tearfully, a stark contrast to his usual stoicism. I'd feared this moment since witnessing Maaci weep months earlier. I had never seen him cry. Now, in the empty house, the loss of this woman brought out emotions in my father that I'd never seen before.

My final visit to Maaci occurred at Henry Ford Hospital on a sun-drenched Friday. En route, I listened to another of Maaci’s favorite songs: "Chalo Dildar Chalo Chand Ke Par Chalo,"—meaning Come Darling Come, Let’s Go Beyond the Moon—from the album Rang Barang, meaning versicolored in Urdu.

Entering the hospital room, I found her in a peaceful slumber and thinner than ever. I watched her little chest rise, filled with air, before letting it out again, rhythmically for hours. We conversed in a circle around Maaci, discussing the aura surrounding her. She offered me a glimpse into my own identity more than anything or anyone before–a descendant of immigrants like her, individuals who relentlessly faced adversities, worked incredibly hard, held no fear, all while striving to offer their successors, the first generation born in their new country like me, the promise of opportunity.

I departed the hospital alone, with my grandmother collecting me as my father stayed behind. I turned to Maaci, asleep and sprawled over a small hospital bed, and simply said, "I love you, Maaci. I’ll see you soon." Nothing more. I like to think that amidst her slumber, nestled within her consciousness, she somehow caught wind of my simple farewell.

I would never see the woman who brought my family to America again. Maaci departed from the world and the family she impacted so deeply on the following Wednesday, leaving a palpable void, akin to the emptiness felt in her house. She never relied on clichés or dispensed life advice, yet within her life I discovered more of my identity than I could have ever imagined. Somehow, I was grateful for the previous year despite its painful end. I was privy to the end of a winding journey, and I learned from it.

No religion can truly attest to what may happen when one departs their earthly abode. My mother’s Catholicism would assert that the righteous ascend to Heaven, while my father’s Hinduism would attest to the concept of rebirth. Maaci’s ashes were scattered in the Detroit River, dispersed before the city which she made hers. I imagine her in a wonderful realm, with her parents and her family, gathered in her home where she would be happiest.

Returning to the house on the hill, I stumbled upon Maaci’s notebooks chronicling her medications and occasional poignant notes. Flipping through, I chanced upon a page, adorned with a Hindu Om and filled with a quote handwritten by Maaci:

ॐ

Find your self

Doubting how far

You can go

Remember How

FAR you have come

Remember Every things

you have Faced

all the Battles you have won

and all the Fears you have overcome

A Brief Note

I am so grateful for the time I spent with Maaci, even when it meant witnessing the end of an incredible woman’s journey. My experience with her made me curious about the Indian community in Michigan—a community Maaci joined and helped create. Maaci has been a great inspiration in the establishment of Little India of Michigan. For me, this Newsletter is a celebration and an acknowledgment of the incredible people, establishments, and culture that characterize the Indian diaspora. I am so proud of my Maaci and the community I am part of thanks to her. I love you forever, Maaci.